2.5 Una combinazione di effetti

È particolarmente importante considerare gli impatti cumulativi delle attività petrolifere e di estrazione del gas in mare aperto. Questo in riferimento sia alla combinazione degli impatti negativi di un singolo progetto, che può influire sulle stesse specie e sugli stessi habitat in diversi modi durante l'intero processo, sia al modo in cui tutti gli impatti delle attività petrolifere e di estrazione del gas in mare aperto si combinano con altre pressioni - passate, presenti e future - sull'ambiente marino, esacerbando gli effetti complessivi.125

petrolifere e di estrazione del gas in mare aperto. Questo in riferimento sia alla combinazione degli impatti negativi di un singolo progetto, che può influire sulle stesse specie e sugli stessi habitat in diversi modi durante l'intero processo, sia al modo in cui tutti gli impatti delle attività petrolifere e di estrazione del gas in mare aperto si combinano con altre pressioni - passate, presenti e future - sull'ambiente marino, esacerbando gli effetti complessivi.125

Una delle principali difficoltà legate agli impatti cumulativi è che sono difficili da attribuire, misurare e monitorare nel tempo e quindi molto difficili da mitigare.126,127 Inoltre, sono spesso sottovalutati.

È importante notare che gli impatti dell'inquinamento, della perdita di habitat e del rumore causati dallo sfruttamento di petrolio e gas sono aggravati anche dalle pressioni aggiuntive dei cambiamenti climatici,128 in particolare dall'aumento della temperatura del mare e dai cambiamenti nella chimica degli oceani.129 Ad esempio, con l'aumento della temperatura del mare, i livelli di ossigeno possono diminuire, rendendo le barriere coralline di acqua fredda più vulnerabili agli effetti dell'acidificazione degli oceani.130 Ciò può portare all'indebolimento della struttura [rocciosa di carbonato di calcio, ndt] delle colonie coralline, rendendole più suscettibili ai danni causati dalle attività di sviluppo e meno resistenti agli effetti dell'inquinamento.128 L'acidificazione degli oceani sta inoltre aumentando la tossicità degli inquinanti da metalli pesanti e amplificando il loro impatto sugli organismi marini.131 È importante considerare l'impatto dei nuovi progetti di sfruttamento di petrolio e gas nel contesto sia dei progetti esistenti che di tutti gli altri impatti sul nostro ambiente marino. È urgentemente necessario un approccio più olistico alla valutazione e alla mitigazione degli impatti cumulativi degli sviluppi offshore 132.

CASI DI STUDIO SU SPECIE E HABITAT

Comunità di spugne di acque profonde

Le comunità di spugne di acque profonde sono colorate, diversificate e con forme e consistenze molto varie. Esse creano hotspot di biodiversità nel mare profondo 260 e importanti zone di riproduzione dei pesci.22 Tuttavia, l'impatto del petrolio e del gas sta portando alla perdita di questo habitat e ad un grave degrado che richiederà decenni, se non secoli, per essere recuperato 22.

Le comunità di spugne forniscono diversi servizi ecosistemici 261 e svolgono un ruolo importante nel ciclo dei nutrienti.262 Nelle aggregazioni di spugne della Area Protetta Marina del Canale delle Faroe-Shetland nord-orientale 263 si trovano fino a 50 specie di spugne e questi habitat strutturalmente diversificati ospitano molte altre specie, tra cui brittlestars, brachiopodi (rari animali bivalvi non imparentati con i molluschi), aragoste nane e vermi tubiformi.264

Le comunità di spugne delle acque profonde sono riconosciute dalla Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR) come ecosistemi marini vulnerabili 265,266 e habitat minacciati/in declino 222. Questi habitat poco conosciuti stanno appena iniziando ad essere compresi dagli scienziati, e le spugne recentemente scoperte e i batteri ad esse associati hanno prodotto nuovi composti farmaceutici.267

Tuttavia, le pressioni antropiche, comprese quelle associate alle attività petrolifere e di estrazione del gas in mare aperto, aggravate dagli impatti climatici, potrebbero causare l'esaurimento di queste specie e compromettere la potenza dei preziosi composti che producono.268 Le comunità di spugne sono particolarmente vulnerabili alla perdita diretta dell'habitat a causa delle attività di trivellazione,269 con studi che dimostrano la perdita completa dell'habitat entro 200 metri dalla trivellazione.74 Le spugne vengono soffocate completamente e muoiono o sono parzialmente ricoperte di sedimenti, che ostacolano la filtrazione e la respirazione 270, oppure sopravvivono in uno stato compromesso.22

Tuttavia, le pressioni antropiche, comprese quelle associate alle attività petrolifere e di estrazione del gas in mare aperto, aggravate dagli impatti climatici, potrebbero causare l'esaurimento di queste specie e compromettere la potenza dei preziosi composti che producono.268 Le comunità di spugne sono particolarmente vulnerabili alla perdita diretta dell'habitat a causa delle attività di trivellazione,269 con studi che dimostrano la perdita completa dell'habitat entro 200 metri dalla trivellazione.74 Le spugne vengono soffocate completamente e muoiono o sono parzialmente ricoperte di sedimenti, che ostacolano la filtrazione e la respirazione 270, oppure sopravvivono in uno stato compromesso.22

Le aree ricoperte da detriti di trivellazione potrebbero non mostrare alcun segno di recupero dopo 10 anni. 74 Se vengono utilizzati fluidi di perforazione particolarmente dannosi (sintetici o a base di petrolio), gli impatti sugli habitat delle spugne possono essere rilevati fino a un chilometro di distanza.227 I fluidi di perforazione a base di petrolio sono stati in gran parte eliminati nelle acque del Regno Unito, a seguito delle raccomandazioni dell'OSPAR, ma i loro impatti sono stati gravi e diffusi.271 Gli habitat delle spugne sono a rischio a causa dei progetti sui giacimenti petroliferi di Cambo e Rosebank, con oleodotti che dovrebbero attraversare le principali aree delle spugne. 272,273

Poiché le spugne assorbono sostanze dall'acqua circostante sia sotto forma di materia disciolta che di particelle, esse accumulano le tossine prodotte e possono fungere da specie di monitoraggio, segnalando quando vengono raggiunti livelli elevati.274 Alcune spugne sono relativamente resistenti all'inquinamento da petrolio 275, mentre il petrolio ha danneggiato le membrane di altre. Sono stati segnalati anche danni alla riproduzione e all'insediamento 275 e l'inquinamento da petrolio può anche influire sulla capacità delle spugne di sequestrare il carbonio.276 Importanti specie di spugne in queste comunità, come la Geodia, sono anche sensibili all'aumento della temperatura del mare associato al cambiamento climatico.277

2.6 L’impatto sulle più importanti aree protette

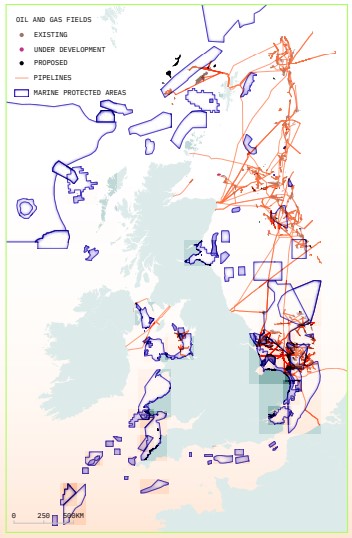

Oggi, lo sfruttamento offshore di petrolio e gas sta minacciando alcune delle iniziative di conservazione marina più importanti del Regno Unito e compromettendo decenni di progressi nella protezione marina, nonché gli sforzi di migliaia di parti interessate e specialisti. Le aree marine protette sono luoghi in mare salvaguardati da attività dannose a beneficio primario della biodiversità e sono sempre più considerate una parte essenziale degli sforzi di conservazione marina del Regno Unito e globali.133 Le evidenze provenienti dal Regno Unito e da tutto il mondo hanno dimostrato come le aree marine altamente protette e gestite in modo efficace possano aumentare la biodiversità su un'area molto più vasta, sostenere la pesca sostenibile,134 migliorare il benessere delle comunità,135 offrire una maggiore resilienza ai cambiamenti climatici 136 e fornire altri importanti servizi a beneficio delle persone e dell'ambiente in generale. Un'area marina protetta (MPA) efficace può anche fornire un rifugio per la riproduzione e l'alimentazione di pesci e molluschi, il che può aumentare le catture nelle zone adiacenti e garantire la sostenibilità a lungo termine della pesca.137 Una MPA ben protetta salvaguarda e migliora anche l'insieme dei servizi ecosistemici che il mare fornisce e dai quali dipendiamo. Queste aree costituiscono anche siti di riferimento che aiutano gli scienziati a comprendere il funzionamento di un ecosistema sano.

Gli obiettivi nazionali e internazionali in materia di azione per il clima stanno portando a una maggiore protezione degli ambienti marini, compreso l'obiettivo di proteggere efficacemente il 30% dei mari entro il 2030, sancito dal recente accordo di Kunming-Montreal.138 Il Regno Unito conta 374 MPA 139 che vanno da alcune piccole aree altamente protette, dove sono vietate tutte le attività di pesca e di sviluppo, ad MPA che attualmente godono di scarsa protezione aggiuntiva dalle attività dannose; tuttavia, la gestione delle MPA sta migliorando. Nel 2022 la pesca con reti a strascico, dannosa per gli ecosistemi, è stata vietata in quattro importanti MPA, tra cui la zona speciale di conservazione del Dogger Bank,144 offrendo agli ecosistemi una protezione più significativa dai danni, e una causa legale da parte di Oceana, un'organizzazione senza scopo di lucro per la conservazione degli oceani, ha costretto il governo a impegnarsi a gestire tutti gli attrezzi da pesca a strascico entro il 2024. Sono inoltre in corso lavori per designare nuove aree marine altamente protette nelle acque inglesi 145 e scozzesi 146, offrendo una protezione molto più efficace. Molte organizzazioni, tra cui Oceana, la Marine Conservation Society e Rewilding Britain 147, stanno promuovendo la classificazione del 30% delle acque del Regno Unito come aree marine altamente protette entro il 2030.

Society e Rewilding Britain 147, stanno promuovendo la classificazione del 30% delle acque del Regno Unito come aree marine altamente protette entro il 2030.

Questa preziosa e crescente rete di MPA del Regno Unito, tuttavia, è minacciata dallo sviluppo di petrolio e gas. Gli attuali sviluppi petroliferi e del gas offshore si verificano all'interno o in prossimità di molti dei nostri siti più importanti,143 e vengono ora rilasciate nuove licenze che invaderanno le aree protette. Un'analisi di Uplift mostra che, nell'ultima tornata di licenze per petrolio e gas offshore 140, 352, ovvero ben oltre un terzo delle quasi 900 località offerte per lo sviluppo, rientrano o si sovrappongono a MPA designate. 166 di questi siti si trovano interamente all'interno di una zona protetta. Questo nonostante la prassi internazionale nella gestione delle Aree Marine Protette affermi chiaramente che l'estrazione di petrolio e gas e altre forme di estrazione mineraria offshore sono incompatibili con MPA effettive.141,142

2.7 I rischi per il carbonio blu: una soluzione climatica emergente

La salute dei mari svolge un ruolo fondamentale nell'azione per il clima 18. La capacità delle specie e degli habitat marini di catturare e immagazzinare carbonio e contribuire a frenare il cambiamento climatico è minacciata dall'impatto delle attività petrolifere e di estrazione del gas in mare aperto e dagli effetti climatici che queste aggravano.156 Nel 2022 il Comitato britannico sui cambiamenti climatici ha raccomandato al Regno Unito di rafforzare la protezione e il ripristino dell'ambiente marino e di sostenere gli sforzi per una gestione sostenibile degli ecosistemi marini e costieri, “tenendo in debita considerazione il loro valore in termini di carbonio” 157.

Il concetto di carbonio blu ha acquisito rilevanza solo nell'ultimo decennio 158, e l'importanza del carbonio depositato nei sedimenti marini e catturato dalle specie e dagli habitat marini è ora riconosciuta come una delle principali soluzioni naturali al cambiamento climatico 159,160. Attualmente, gli habitat del carbonio blu presenti nel Regno Unito più conosciuti e studiati sono le praterie marine e le paludi salmastre, che sono ora al vaglio per diventare i primi habitat marini ad essere inclusi nell'inventario nazionale dei gas serra del Regno Unito.161 Anche le alghe marine, come le foreste di kelp, possono svolgere un ruolo nel sequestro del carbonio, sebbene la ricerca in questo campo sia ancora in fase di sviluppo. 162 In futuro, la protezione e il miglioramento di questi habitat non saranno importanti solo per la conservazione 163, ma anche per la rendicontazione internazionale delle emissioni e il rispetto degli obiettivi di riduzione delle emissioni nazionali e internazionali.164-166

Le paludi salmastre e le praterie marine sono entrambe habitat costieri, quindi sono più a rischio per le grandi fuoriuscite accidentali di petrolio che raggiungono la costa 167, o per la perdita di habitat associata al trasporto di petrolio e gas verso la costa, causata da oleodotti, raffinerie e infrastrutture portuali.168 Le praterie di alghe marine intorno al Regno Unito sono state notevolmente ridotte dalle attività umane nel corso dell'ultimo secolo 155,169 e sono anche a rischio per gli eventi di calore estremo 170, resi più probabili e più gravi dai cambiamenti climatici. In termini di accumulo totale di carbonio, sono i sedimenti marini ad avere la maggiore capacità. Sono stati condotti studi approfonditi in Scozia 171,172 e più a sud, nel Mare del Nord inglese 173, che hanno dimostrato l'importanza dei sedimenti offshore 157 nello stoccaggio del carbonio. Una delle minacce agli habitat del carbonio blu è la pesca con reti a strascico e draghe, ma questo danno sta cominciando ad essere affrontato in alcune delle MPA del Regno Unito, ad esempio con le nuove restrizioni alla pesca recentemente introdotte nel Dogger Bank.144

Gli impatti delle attività petrolifere e del gas offshore devono ora essere attentamente valutati anche dal punto di vista del carbonio blu.173 Gli habitat del carbonio blu possono andare persi direttamente quando si trovano nell'area di sviluppo di un progetto petrolifero e del gas o sono colpiti da un grave incidente petrolifero. Sono inoltre a rischio di soffocamento e contaminazione a lungo termine da parte dei rifiuti e delle tossine rilasciati durante le operazioni. Il carbonio blu è immagazzinato anche negli animali marini e studi recenti hanno evidenziato come i pesci di grandi dimensioni 174 e i mammiferi marini 175 che muoiono naturalmente e affondano sui fondali delle zone di mare profondo possano costituire un importante serbatoio di carbonio. Questo lavoro è ancora in fase di sviluppo ed è improbabile che il carbonio blu venga incluso negli inventari nel prossimo futuro,176 ma evidenzia la complessità delle soluzioni climatiche basate sulla natura e l'importanza di ecosistemi sani.

Come abbiamo visto, l'inquinamento e il disturbo associati alle attività petrolifere e di estrazione del gas in mare aperto possono avere un impatto sui mammiferi marini, compresi alcuni dei nostri animali più grandi come le balenottere boreali e le balenottere comuni, che si nutrono e migrano in alcune aree caratterizzate da un'attività petrolifera e di estrazione del gas molto intensa. Sebbene questi impatti raramente uccidano direttamente le balene e i pesci di grandi dimensioni, riducono comunque la loro capacità di riprodursi. L'aumento degli impatti dei cambiamenti climatici 177,178 ridurrà anche le popolazioni future e il carbonio complessivo che alla fine verrà immagazzinato nelle profondità marine. Sebbene la scienza del carbonio blu sia ancora in fase di sviluppo e gli impatti sulle riserve di carbonio blu non siano ancora stati ufficialmente quantificati, è chiaro che l'estrazione di petrolio e gas in mare aperto sta già influenzando il carbonio blu in innumerevoli modi, rendendolo un fattore chiave da considerare nelle future decisioni relative alle licenze.

2.9 Perpetuando l'inquinamento da plastica

Anche il petrolio e il gas offshore stanno dando un grande contributo alla crisi della plastica negli oceani. L'impatto dei rifiuti marini onnipresenti e in particolare dell'inquinamento da plastica è stato al centro dell'attenzione per la conservazione degli oceani negli ultimi anni 199,200 e la produzione di plastica è una delle principali fonti di emissioni di gas serra.201 Sebbene il collegamento non sia sempre evidente, ci sono due modi principali in cui l'industria petrolifera e del gas offshore contribuisce all'inquinamento da plastica: 1) le microplastiche utilizzate nell'industria petrolifera e del gas offshore e 2) la plastica prodotta dai prodotti dell'industria petrolifera e del gas. In primo luogo, le microplastiche sono utilizzate nell'industria petrolifera e del gas offshore all’interno di prodotti quali demulsificanti e inibitori di corrosione che vengono scaricati nell'ambiente marino.202 È stato stimato che nel 2016 oltre 100 tonnellate di microplastiche sono state rilasciate nel Mare del Nord dalle attività petrolifere e del gas 203. Inoltre, studi sui sedimenti e sulle creature marine in prossimità degli impianti hanno evidenziato livelli di microplastiche significativamente più elevati rispetto ad altre zone 204. La plastica ha un impatto su alcuni dei nostri habitat più preziosi; una ricerca ha dimostrato che l'11% dei campioni di creature marine provenienti dall'area marina protetta di East Mingulay nelle Ebridi ha ingerito microplastiche 205.

sempre evidente, ci sono due modi principali in cui l'industria petrolifera e del gas offshore contribuisce all'inquinamento da plastica: 1) le microplastiche utilizzate nell'industria petrolifera e del gas offshore e 2) la plastica prodotta dai prodotti dell'industria petrolifera e del gas. In primo luogo, le microplastiche sono utilizzate nell'industria petrolifera e del gas offshore all’interno di prodotti quali demulsificanti e inibitori di corrosione che vengono scaricati nell'ambiente marino.202 È stato stimato che nel 2016 oltre 100 tonnellate di microplastiche sono state rilasciate nel Mare del Nord dalle attività petrolifere e del gas 203. Inoltre, studi sui sedimenti e sulle creature marine in prossimità degli impianti hanno evidenziato livelli di microplastiche significativamente più elevati rispetto ad altre zone 204. La plastica ha un impatto su alcuni dei nostri habitat più preziosi; una ricerca ha dimostrato che l'11% dei campioni di creature marine provenienti dall'area marina protetta di East Mingulay nelle Ebridi ha ingerito microplastiche 205.

L'ingestione di plastica provoca una serie di effetti negativi sulle specie, dalla riduzione delle riserve energetiche 206 alla morte 207. Mancano ancora ricerche e quindi conoscenze sull'impatto dell'inquinamento da plastica sugli ecosistemi, ma permangono preoccupazioni circa l'effetto della plastica sulla capacità di carbonio blu 208 e su altri servizi ecosistemici, compresa la contaminazione dei prodotti ittici e i rischi per la salute pubblica ad essa associati 209. In secondo luogo, la plastica è prodotta con prodotti dell'industria petrolifera e del gas, e questi due settori sono strettamente collegati 210. È stato ampiamente riportato come le imprese petrolifere e del gas stiano promuovendo sempre più l'uso dei loro prodotti nell'industria della plastica e investendo in infrastrutture petrolchimiche, dato che la domanda di carburante per il trasporto e il riscaldamento sta diminuendo 211,212. Nonostante i crescenti impegni nazionali e internazionali per ridurre i rifiuti di plastica e promuovere il riutilizzo e il riciclaggio della plastica, l'uso commerciale della plastica monouso continua a crescere in molti settori 213 e gli investimenti nell'industria petrolchimica sono in aumento 214. A titolo illustrativo, nel 2019 il 3,9% dei ricavi della Shell proveniva dai prodotti petrolchimici, percentuale che è salita al 6,5% nel 2020 215. Si prevede che entro il 2030 l'industria petrolchimica rappresenterà oltre un terzo della crescita prevista della domanda di petrolio 216. Questa attenzione all'aumento della produzione di plastica da combustibili fossili, piuttosto che al riciclaggio dei materiali esistenti o allo sviluppo di opzioni riutilizzabili, ha gravi implicazioni per il mare e sta alimentando la crescente crisi dei rifiuti marini e dell'inquinamento da plastica nelle acque del Regno Unito e a livello internazionale 201.

(4. Continua)

* Traduzione di Ecor.Network

In Deep Water: Exposing the hidden impacts of oil and gas on the UK’s seas

Oceana, Uplift

Aprile 2023, 45 pp.

Download:

Note:

1. Galparsoro, I. et al. Reviewing the ecological impacts of offshore wind farms. npj Ocean Sustainability 1, 1 (2022).

2. Marappan, S., Stokke, R., Malinovsky, M.P., & Taylor, A. Assessment of impacts of the offshore oil and gas industry on the marine environment. in OSPAR, 2023: The 2023 Quality Status Report for the North-East Atlantic. (OSPAR Commission, 2022).

3. Welsby, D., Price, J., Pye, S. & Ekins, P. Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5 °C world. Nature 597, 230–234 (2021).

4. IEA. Net Zero by 2050. https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050 (2021).

5. BEIS/Prime Minister’s Office. UK enshrines new target in law to slash emissions by 78% by 2035. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-enshrines-new-target-in-law-to-slash-emissions-by-78-by-2035 (2021).

6. UNFCCC. The Paris Agreement. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement (Undated).

7. Supran, G., Rahmstorf, S. & Oreskes, N. Assessing ExxonMobil’s global warming projections. Science 379, eabk0063.

8. Franta, B. Early oil industry disinformation on global warming. Environmental Politics 30, 663–668 (2021).

9. ExxonMobil. https://www.exxonmobil.co.uk/company/overview/uk-operations/production. (2019).

10. McCauley, D. J. et al. Marine defaunation: Animal loss in the global ocean. Science 347, 1255641 (2015).

11. Worm, B. et al. Impacts of Biodiversity Loss on Ocean Ecosystem Services. Science 314, 787–790 (2006).

12. Palumbi, S. R. et al. Managing for ocean biodiversity to sustain marine ecosystem services. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 7, 204–211 (2009).

13. Hoegh-Guldberg, O. et al. The ocean as a solution to climate change: Five opportunities for action. (2019).

14. Smale, D. A., Burrows, M. T., Moore, P., O’Connor, N. & Hawkins, S. J. Threats and knowledge gaps for ecosystem services provided by kelp forests: a northeast Atlantic perspective. Ecology and Evolution 3, 4016–4038 (2013).

15. Ondiviela, B. et al. The role of seagrasses in coastal protection in a changing climate. Coastal Engineering 87, 158–168 (2014).

16. Bloor, I. S. M. et al. Boom not bust: Cooperative management as a mechanism for improving the commercial efficiency and environmental outcomes of regional scallop fisheries. Marine Policy 132, 104649 (2021).

17. Avdelas, L. et al. The decline of mussel aquaculture in the European Union: causes, economic impacts and opportunities. Reviews in Aquaculture 13, 91–118 (2021).

18. Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Northrop, E. & Lubchenco, J. The ocean is key to achieving climate and societal goals. Science 365, 1372–1374 (2019).

19. Laffoley, D. et al. The forgotten ocean: Why COP26 must call for vastly greater ambition and urgency to address ocean change. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 32, 217–228 (2022).

20. Roberts, C. M. et al. Marine reserves can mitigate and promote adaptation to climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114, 6167 (2017).

21. Duarte, C. M. et al. Rebuilding marine life. Nature 580, 39–51 (2020).

22. Vad, J. et al. Chapter Two - Potential Impacts of Offshore Oil and Gas Activities on Deep-Sea Sponges and the Habitats They Form. in Advances in Marine Biology (ed. Sheppard, C.) vol. 79 33–60 (Academic Press, 2018).

23. Animah, I. & Shafiee, M. Condition assessment, remaining useful life prediction and life extension decision making for offshore oil and gas assets. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 53, 17–28 (2018).

24. Hjorth, M. et al. Effects of Oil and Gas Production On Marine Ecosystems and Fish Stocks in the Danish North Sea: Review. Report for WSP Denmark. https://mst.dk/media/222352/oil_gas-effect-report_final.pdf (2021).

25. Stowe, T. J. & Underwood, L. A. Oil spillages affecting seabirds in the United Kingdom, 1966–1983. Marine Pollution Bulletin 15, 147–152 (1984).

26. Moore, J., Taylor, P. & Hiscock, K. Rocky shores monitoring programme. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section B. Biological Sciences 103, 181–200 (1995).

27. Riddick, S. N. et al. Methane emissions from oil and gas platforms in the North Sea. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 19, 9787–9796 (2019).

28. Cordes, E. E. et al. Environmental Impacts of the Deep-Water Oil and Gas Industry: A Review to Guide Management Strategies. Frontiers in Environmental Science 4, (2016).

29. Frost, K. J. et al. Alaska, and Adjacent Areas Following the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Marine Mammal Study Number 5. (1994).

30. Garrott, R. A., Eberhardt, L. L. & Burn, D. M. Mortality of sea otters in Prince William Sound following the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Marine Mammal Science 9, 343–359 (1993).

31. Kerr, R., Kintisch, E. & Stokstad, E. Will Deepwater Horizon Set a New Standard for Catastrophe? Science 328, 674–675 (2010).

32. Montagna, P. A. et al. Deep-Sea Benthic Footprint of the Deepwater Horizon Blowout. PLOS ONE 8, e70540 (2013).

33. Bodkin JL et al. Long-term effects of the Exxon Valdez oil spill: sea otter foraging in the intertidal as a pathway of exposure to lingering oil. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 447, 273–287 (2012).

34. Heintz, R. A., Short, J. W. & Rice, S. D. Sensitivity of fish embryos to weathered crude oil: Part II. Increased mortality of pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) embryos incubating downstream from weathered Exxon valdez crude oil. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 18, 494–503 (1999).

35. Matkin, C. O., Saulitis, E. L., Ellis, G. M., Olesiuk, P. & Rice, S. D. Ongoing population-level impacts on killer whales Orcinus orca following the ‘Exxon Valdez’ oil spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Marine Ecology Progress Series 356, 269–281 (2008).

36. Muehlenbachs, L., Cohen, M. A. & Gerarden, T. The impact of water depth on safety and environmental performance in offshore oil and gas production. Energy Policy 55, 699–705 (2013).

37. Gallego, A. et al. Current status of deepwater oil spill modelling in the Faroe-Shetland Channel, Northeast Atlantic, and future challenges. Marine Pollution Bulletin 127, 484–504 (2018).

38. Jernelov, A. The threats from oil spills: now, then, and in the future. Ambio 39, 353–366 (2010).

39. Moore, J. et al. SEA EMPRESS SPILL: IMPACTS ON MARINE AND COASTAL HABITATS. International Oil Spill Conference Proceedings 1997, 213–216 (1997).

40. Banks, A. N. et al. The Sea Empress oil spill (Wales, UK): Effects on Common Scoter Melanitta nigra in Carmarthen Bay and status ten years later. Marine Pollution Bulletin 56, 895–902 (2008).

41. Webster, L. et al. Long-term Monitoring of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Mussels (Mytilus edulis) Following the Braer Oil Spill†. Analyst 122, 1491–1495 (1997).

42. Conroy, J. & Kruuk, H. Changes in Otter Numbers in Shetland Between 1988 and 1993. Oryx vol. 29 197–204 (1995).

43. Hall, A. J., Watkins, J. & Hiby, L. The impact of the 1993 Braer oil spill on grey seals in Shetland. Science of The Total Environment 186, 119–125 (1996).

44. Goodlad, J. Effects of the Braer oil spill on the Shetland seafood industry. Science of The Total Environment 186, 127–133 (1996).

45. Equinor. Rosebank Environmental Statement ES/2022/001.

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1097880/Rosebank_Environmental_Statement_-_Final_for_Submission_To_OPRED_Equinor_3rd_August_2022.pdf (2022).

46. Baker, J. R., Jones, A. M., Jones, T. P. & Watson, H. C. Otter Lutra lutra L. mortality and marine oil pollution. Biological Conservation 20, 311–321 (1981).

47. Joye, S. B. et al. The Gulf of Mexico ecosystem, six years after the Macondo oil well blowout. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 129, 4–19 (2016).

48. Law, R. J. & Hellou, J. Contamination of Fish and Shellfish Following Oil Spill Incidents. Environmental Geosciences 6, 90–98 (1999).

49. Bakhmet, I., Fokina, N. & Ruokolainen, T. Changes of Heart Rate and Lipid Composition in Mytilus Edulis and Modiolus Modiolus Caused by Crude Oil Pollution and Low Salinity Effects. J Xenobiot 11, 46–60 (2021).

50. Farinas-Franco, J. M. et al. Are we there yet? Management baselines and biodiversity indicators for the protection and restoration of subtidal bivalve shellfish habitats. Science of The Total Environment 863, 161001 (2023).

51. DeLeo, D. M., Ruiz-Ramos, D. V., Baums, I. B. & Cordes, E. E. Response of deep-water corals to oil and chemical dispersant exposure. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 129, 137–147 (2016).

52. DeLeo, D. M., Lengyel, S. D. & Cordes, E. E. Assessing Oil Spill Impacts to Cold-Water Corals of the Deep Gulf of Mexico. 2016, PO13F-05 (2016).

53. OSPAR. Assessment of the OSPAR Report on Discharges, Spills and Emissions from Offshore Installations 2009 – 2018.

54. OSPAR. OSPAR report on discharges, spills and emissions from offshore oil and gas installations in 2012.

55. Dong, Y., Liu, Y., Hu, C., MacDonald, I. R. & Lu, Y. Chronic oiling in global oceans. Science 376, 1300–1304 (2022).

56. Camphuysen, K. C. J. Declines in oil-rates of stranded birds in the North Sea highlight spatial patterns in reductions of chronic oil pollution. Marine Pollution Bulletin 60, 1299–1306 (2010).

57. Camphuysen, K. & Heubeck, M. Beached Bird Surveys in the North Sea as an Instrument to Measure Levels of Chronic Oil Pollution. In Oil Pollution in the North Sea (ed. Carpenter, A.) 193–208 (Springer International Publishing, 2016). doi:10.1007/698_2015_435.

58. Neff, J., Lee, K. & DeBlois, E. M. Produced Water: Overview of Composition, Fates, and Effects. in Produced Water: Environmental Risks and Advances in Mitigation Technologies (eds.Lee, K. & Neff, J.) 3–54 (Springer New York, 2011). doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0046-2_1.

59. OSPAR. Report on impacts of discharges of oil and chemicals in produced water on the marine environment. https://www.ospar.org/documents?v=47303 (2021).

60. Bakke, T., Klungsoyr, J. & Sanni, S. Environmental impacts of produced water and drilling waste discharges from the Norwegian offshore petroleum industry. Marine Environmental Research 92, 154–169 (2013).

61. Hansen, B. H. et al. Embryonic exposure to produced water can cause cardiac toxicity and deformations in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) and haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) larvae. Marine Environmental Research 148, 81–86 (2019).

62. Meier, S. et al. DNA damage and health effects in juvenile haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) exposed to PAHs associated with oil-polluted sediment or produced water. PLOS ONE 15, e0240307 (2020).

63. Neff, J. M. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the aquatic environment. Biol. Conserv.;(United Kingdom) 18, (1980).

64. Tuvikene, A. Responses of fish to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Annales Zoologici Fennici 32, 295–309 (1995).

65. Sundt, R. C., Pampanin, D. M., Grung, M., Baršienė, J. & Ruus, A. PAH body burden and biomarker responses in mussels (Mytilus edulis) exposed to produced water from a North Sea oil field: Laboratory and field assessments. Marine Pollution Bulletin 62, 1498–1505 (2011).

66. Capuzzo, J. M., Lancaster, B. A. & Sasaki, G. C. The effects of petroleum hydrocarbons on lipid metabolism and energetics of larval development and metamorphosis in the american lobster (homarus americanus Milne Edwards). Marine Environmental Research 14, 201–228 (1984).

67. Kho, F. et al. Current understanding of the ecological risk of mercury from subsea oil and gas infrastructure to marine ecosystems. Journal of Hazardous Materials 438, 129348 (2022).

68. Al-Kindi, S., Al-Bahry, S., Al-Wahaibi, Y., Taura, U. & Joshi, S. Partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide: enhanced oil recovery applications, oil-field produced water pollution, and possible solutions. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 194, 875 (2022).

69. Xiong, B. et al. Polyacrylamide degradation and its implications in environmental systems. npj Clean Water 1, 1–9 (2018).

70. Cruz, A. M. & Krausmann, E. Vulnerability of the oil and gas sector to climate change and extreme weather events. Climatic Change 121, 41–53 (2013).

71. Santos, M. F. L., Lana, P. C., Silva, J., Fachel, J. G. & Pulgati, F. H. Effects of non-aqueous fluids cuttings discharge from exploratory drilling activities on the deep-sea macrobenthic communities. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 56, 32–40 (2009).

72. Veltman, K., Huijbregts, M. A., Rye, H. & Hertwich, E. G. Including impacts of particulate emissions on marine ecosystems in life cycle assessment: The case of offshore oil and gas production. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 7, 678–686 (2011).

73. Taylor, J., Drewery, J., & Boulcott, P. 1218S Cruise Report: Monitoring survey of Faroe-Shetland Sponge Belt NCMPA, Rosemary Bank Seamount NCMPA and Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC, (2019).

74. Jones DOB, Gates AR, & Lausen B. Recovery of deep-water megafaunal assemblages from hydrocarbon drilling disturbance in the Faroe−Shetland Channel. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 461, 71–82 (2012).

75. Duarte, C. M. et al. The soundscape of the Anthropocene ocean. Science 371, eaba4658 (2021).

76. Krause, B. Voices of the wild: animal songs, human din, and the call to save natural soundscapes. (Yale University Press, 2015).

77. Williams, W.J., Curnick, D.J., & Deaville, R. (last). Identification of key species in the UK, with a focus on English waters, sensitive to underwater noise, (2021).

78. Chou, E., Southall, B. L., Robards, M. & Rosenbaum, H. C. International policy, recommendations, actions and mitigation efforts of anthropogenic underwater noise. Ocean & Coastal Management 202, 105427 (2021).

79. Rako-Gospi, N. & Picciulin, M. Chapter 20 - Underwater Noise: Sources and Effects on Marine Life. in World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation (Second Edition) (ed. Sheppard, C.) 367–389 (Academic Press, 2019).

80. Mooney, T. A., Andersson, M. H. & Stanley, J. Acoustic impacts of offshore wind energy on fishery resources. Oceanography 33, 82–95 (2020).

81. Nowacek, D. P. et al. Marine seismic surveys and ocean noise: time for coordinated and prudent planning. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 13, 378–386 (2015).

82. Erbe, C., Duncan, A., Hawkins, L., Terhune, J. M. & Thomas, J. A. Introduction to Acoustic Terminology and Signal Processing. in Exploring Animal Behavior Through Sound: Volume 1 111–152 (Springer, 2022).

83. Nieukirk, S. L. et al. Sounds from airguns and fin whales recorded in the mid-Atlantic Ocean, 1999–2009. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 131, 1102–1112 (2012).

84. McCauley, R. D. et al. Widely used marine seismic survey air gun operations negatively impact zooplankton. Nat Ecol Evol 1, 1–8 (2017).

85. Mann, D. et al. Hearing Loss in Stranded Odontocete Dolphins and Whales. PLOS ONE 5, e13824 (2010).

86. Kavanagh, A. S., Nykanen, M., Hunt, W., Richardson, N. & Jessopp, M. J. Seismic surveys reduce cetacean sightings across a large marine ecosystem. Sci Rep 9, 19164 (2019).

87. Castellote, M. & Llorens, C. Review of the Effects of Offshore Seismic Surveys in Cetaceans: Are Mass Strandings a Possibility? in The Effects of Noise on Aquatic Life II (eds. Popper, A. N. & Hawkins, A.) 133–143 (Springer New York, 2016).

88. Lucke, K., Siebert, U., Lepper, P. A. & Blanchet, M.-A. Temporary shift in masked hearing thresholds in a harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) after exposure to seismic airgun stimuli. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 125, 4060–4070 (2009).

89. Pirotta, E., Brookes, K. L., Graham, I. M. & Thompson, P. M. Variation in harbour porpoise activity in response to seismic survey noise. Biology Letters 10, 20131090 (2014).

90. Gordon, J. C. D. et al. A Review of the Effects of Seismic Survey on Marine Mammals. Marine Technology Society Journal 37, (2003).

91. Stone, C. J. The effects of seismic activity on marine mammals in UK waters, 1998-2000, (2003).

92. Stone, C. J., Hall, K., Mendes, S. & Tasker, M. L. The effects of seismic operations in UK waters: analysis of Marine Mammal Observer data. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management (2017).

93. Dunlop, R. A. et al. The behavioural response of migrating humpback whales to a full seismic airgun array. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 284, 20171901 (2017).

94. McCauley, R. D. et al. MARINE SEISMIC SURVEYS— A STUDY OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPLICATIONS. The APPEA Journal 40, 692–708 (2000).

95. Wisniewska, D. M. et al. Ultra-High Foraging Rates of Harbor Porpoises Make Them Vulnerable to Anthropogenic Disturbance. Current Biology 26, 1441–1446 (2016).

96. Nelms, S. E., Piniak, W. E. D., Weir, C. R. & Godley, B. J. Seismic surveys and marine turtles: An underestimated global threat? Biological Conservation 193, 49–65 (2016).

97. Soto, N. A. et al. Anthropogenic noise causes body malformations and delays development in marine larvae. Sci Rep 3, 1–5 (2013).

98. Guerra, A., Gonzalez, A. & Rocha, F. A review of records of giant squid in the north-eastern Atlantic and severe injuries in Architeuthis dux stranded after acoustic exploration. ICES CM 2004, (2004).

99. Sole, M., Monge, M., Andre, M. & Quero, C. A proteomic analysis of the statocyst endolymph in common cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis): an assessment of acoustic trauma after exposure to sound. Scientific Reports 9, 9340 (2019).

100. Day, R. D., McCauley, R. D., Fitzgibbon, Q. P., Hartmann, K. & Semmens, J. M. Seismic air guns damage rock lobster mechanosensory organs and impair righting reflex. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 286, 20191424 (2019).

101. Andre, M. et al. Low-frequency sounds induce acoustic trauma in cephalopods. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 9, 489–493 (2011).

102. Davidsen, J. G. et al. Effects of sound exposure from a seismic airgun on heart rate, acceleration and depth use in free-swimming Atlantic cod and saithe. Conservation Physiology 7, coz020 (2019).

103. Sierra-Flores, R., Atack, T., Migaud, H. & Davie, A. Stress response to anthropogenic noise in Atlantic cod Gadus morhua L. Aquacultural Engineering 67, 67–76 (2015).

104. Engas, A. & Lokkeborg, S. Effects of seismic shooting and vessel-generated noise on fish behaviour and catch rates. Bioacoustics 12, 313–316 (2002).

105. Lokkeborg, S., Ona, E., Vold, A. & Salthaug, A. Sounds from seismic air guns: gear- and species-specific effects on catch rates and fish distribution. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 69, 1278–1291 (2012).

106. Slotte, A., Hansen, K., Dalen, J. & Ona, E. Acoustic mapping of pelagic fish distribution and abundance in relation to a seismic shooting area off the Norwegian west coast. Fisheries Research 67, 143–150 (2004).

107. Hassel, A. et al. Reaction of sand eel to seismic shooting: A field experiment and fishery statistics study. (2003).

108. Hassel, A. et al. Influence of seismic shooting on the lesser sandeel (Ammodytes marinus). ICES Journal of Marine Science - ICES J MAR SCI 61, 1165–1173 (2004).

109. Merchant, N. D. & Robinson, S. Abatement of underwater noise pollution from pile-driving and explosions in UK waters. in vol. 12 (2019).

110. Dahne, M. et al. Effects of pile-driving on harbour porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) at the first offshore wind farm in Germany. Environmental Research Letters 8, 025002 (2013).

111. Genesis Oil and Gas & Consultants. Review and Assessment of Underwater Sound Produced from Oil and Gas Sound Activities and Potential Reporting Requirements under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, (2011).

112. Fowler, A. M. et al. Environmental benefits of leaving offshore infrastructure in the ocean.Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 16, 571–578 (2018).

113. MacIntosh, A., Dafforn, K., Penrose, B., Chariton, A. & Cresswell, T. Ecotoxicological effects of decommissioning offshore petroleum infrastructure: A systematic review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 52, 3283–3321 (2022).

114. Cantle, P. & Bernstein, B. Air emissions associated with decommissioning California’s offshore oil and gas platforms. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 11, 564–571 (2015).

115. Coolen, J. W. P. et al. Ecological implications of removing a concrete gas platform in the North Sea. Journal of Sea Research 166, 101968 (2020).

116. Stap, T., Coolen, J. W. P. & Lindeboom, H. J. Marine Fouling Assemblages on Offshore Gas Platforms in the Southern North Sea: Effects of Depth and Distance from Shore on Biodiversity. PLOS ONE 11, e0146324 (2016).

117. Ahiaga-Dagbui, D., Whyte, A. & Boateng, P. Costing and Technological Challenges of Offshore Oil and Gas Decommissioning in the UK North Sea. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 143, (2017).

118. Jorgensen, D. OSPAR’s exclusion of rigs-toreefs in the North Sea. Ocean & Coastal Management 58, 57–61 (2012).

119. OSPAR. OSPAR Decision 98/3 on the Disposal of Disused Offshore Installations, (1998).

120. Fortune, I. S. & Paterson, D. M. Ecological best practice in decommissioning: a review of scientific research. ICES Journal of Marine Science 77, 1079–1091 (2020).

121. Tidbury, H. et al. Social network analysis as a tool for marine spatial planning: Impacts of decommissioning on connectivity in the North Sea. Journal of Applied Ecology 57, 566–577 (2020).

122. Ekins, P., Vanner, R. & Firebrace, J. Decommissioning of offshore oil and gas facilities: A comparative assessment of different scenarios. Journal of Environmental Management 79, 420–438 (2006).

123. Aslani, F., Zhang, Y., Manning, D., Valdez, L. C. & Manning, N. Additive and alternative materials to cement for well plugging and abandonment: A state-of-the-art review. Journal of PetroleumScience and Engineering 215, 110728 (2022).

124. North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA). UKCS Decommissioning Cost Estimate 2022, (2022).

125. Hegmann, G. et al. Cumulative Effects Assessment Practitioners Guide. (1999).

126. Kirkfeldt, T. S. et al. Why cumulative impacts assessments of hydrocarbon activities in the Arctic fail to meet their purpose. Reg Environ Change 17, 725–737 (2017).

127. Pirotta, E. et al. Understanding the combined effects of multiple stressors: A new perspective on a longstanding challenge. Science of The Total Environment 821, 153322 (2022).

128. Bindoff, N. L. et al. Changing ocean, marine ecosystems, and dependent communities. IPCC special report on the ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate 477–587 (2019).

129. Gissi, E. et al. A review of the combined effects of climate change and other local human stressors on the marine environment. Science of The Total Environment 755, 142564 (2021).

130. Jackson, E. L., Davies, A. J., Howell, K. L., Kershaw, P. J. & Hall-Spencer, J. M. Future-proofing marine protected area networks for cold water coral reefs. ICES Journal of Marine Science 71, 2621–2629 (2014).

131. Roberts, D. A. et al. Ocean acidification increases the toxicity of contaminated sediments. Global Change Biology 19, 340–351 (2013).

132. Willsteed, E., Gill, A. B., Birchenough, S. N. R. & Jude, S. Assessing the cumulative environmental effects of marine renewable energy developments: Establishing common ground. Science of The Total Environment 577, 19–32 (2017).

133. Laffoley, D. et al. Chapter 29 – Marine Protected Areas. in World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation (Second Edition) (ed. Sheppard, C.) 549–569 (Academic Press, 2019).

134. Roberts, C. M., Bohnsack, J. A., Gell, F., Hawkins, J. P. & Goodridge, R. Effects of Marine Reserves on Adjacent Fisheries. Science 294, 1920–1923 (2001).

135. Ban, N. C. et al. Well-being outcomes of marine protected areas. Nature Sustainability 2, 524–532 (2019).

136. Sheehan, E. V. et al. Rewilding of Protected Areas Enhances Resilience of Marine Ecosystems to Extreme Climatic Events. Frontiers in Marine Science 8, (2021).

137. Gell, F. R. & Roberts, C. M. Benefits beyond boundaries: the fishery effects of marine reserves. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 18, 448–455 (2003).

138. Convention on Biological Diversity. Final text of Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. (2022).

139. JNCC. UK Marine Protected Area Network Statistics, (2022).

140. North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA), Offshore Petroleum Licensing Rounds,(2022).

141. Guidelines for applying the IUCN protected area management categories to marine protected areas. (IUCN).

142. Stolton, S., Shadie, P., & Dudley, N. IUCN WCPA Best Practice Guidance on Recognising Protected Areas and Assigning Management Categories and Governance Types.

143. Burdon, D., Barnard, S., Boyes, S. J. & Elliott, M. Oil and gas infrastructure decommissioning in marine protected areas: System complexity, analysis and challenges. Marine Pollution Bulletin 135, 739–758 (2018).

144. Marine Management Organisation. The Dogger Bank Special Area of Conservation (Specified Area) Bottom Towed Fishing Gear Byelaw 2022, (2022).

145. JNCC. English Highly Protected Marine Areas. (2022).

146. Scottish Government. Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs) - site selection: draft guidelines. / (2022).

147. Marine Conservation Society & Rewilding Britain. Marine Conservation Society & Rewilding Britain. (2022) Blue carbon: Ocean-based solutions to fight the climate crisis. A report by the Marine Conservation Society and Rewilding Britain. (2022).

148. Grorud-Colvert, K. et al. The MPA Guide: A framework to achieve global goals for the ocean. Science 373, eabf0861 (2021).

149. Santo, E. M. D. Assessing public participation in environmental decision-making: Lessons learned from the UK Marine Conservation Zone (MCZ) site selection process. Marine Policy 64, 91–101 (2016).

150. Engel, M. T. & Vaske, J. J. Balancing public acceptability and consensus regarding marine protected areas management using the Potential for Conflict Index2. Marine Policy 139, 105042 (2022).

151. Gies, Erica. Canada Has New Rules Governing Its Marine Protected Areas. Do They Go Far Enough? (2019).

152. DEFRA. Inner Silver Pit South: Consultation factsheet for candidate Highly Protected Marine Area (HPMA). (2022).

153. Gamble, C. et al. Seagrass Restoration Handbook: UK and Ireland. in (Zoological Society of London, 2021).

154. Fodrie, F. J. et al. Oyster reefs as carbon sources and sinks. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 284, 20170891 (2017).

155. Green, A. E., Unsworth, R. K. F., Chadwick, M. A. & Jones, P. J. S. Historical Analysis Exposes Catastrophic Seagrass Loss for the United Kingdom. Frontiers in Plant Science 12, (2021).

156. Lovelock, C. E. & Reef, R. Variable Impacts of Climate Change on Blue Carbon. One Earth 3, 195–211 (2020).

157. Climate Change Committee. Briefing: Blue Carbon-March 2022 Climate Change Committee. (2022).

158. Costa, M. & Macreadie, P. The Evolution of Blue Carbon Science. Wetlands 42, (2022).

159. Claes, J., Hopman, D., Jaeger, G. & Rogers, M. Blue carbon: The potential of coastal and oceanic climate action. (2022).

160. Macreadie, P. I. et al. Blue carbon as a natural climate solution. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2, 826–839 (2021).

161. Burden, Annette & Clilverd, Hannah. Moving towards inclusion of coastal wetlands in the UK LULUCF inventory: rapid assessment of activity data availability. 61 (2022).

162. Krause-Jensen, D. et al. Sequestration of macroalgal carbon: the elephant in the Blue Carbon room. Biology Letters 14, 20180236 (2018).

163. Cullen-Unsworth, L. C. & Unsworth, R. K. Strategies to enhance the resilience of the world’s seagrass meadows. Journal of Applied Ecology 53, 967–972 (2016).

164. Hiraishi, T. et al. 2013 supplement to the 2006 IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories: Wetlands. IPCC, Switzerland (2014).

165. Austin, W., Smeaton, C., Houston, A. & Balke, T. Scottish saltmarsh, sea-level rise, and the potential for managed realignment to deliver blue carbon gains. (2022).

166. Smeaton, C. et al. Using citizen science to estimate surficial soil Blue Carbon stocks in Great British saltmarshes. Frontiers in Marine Science 461 (2022).

167. Boorman, L. Saltmarsh Review. An overview of coastal saltmarshes, their dynamic and sensitivity characteristics for conservation and management. (2003).

168. Davy, A., Bakker, J. & Figueroa, M. Human modification of European salt marshes. Human impacts on salt marshes: a global perspective. University of California Press, Berkeley, California, USA 311–336 (2009).

169. Jones, B. L. & Unsworth, R. K. F. The perilous state of seagrass in the British Isles. Royal Society Open Science 3, 150596.

170. Arias-Ortiz, A. et al. A marine heatwave drives massive losses from the world’s largest seagrass carbon stocks. Nature Climate Change 8, 338–344 (2018).

171. Porter, J. et al. Blue carbon audit of Orkney waters. (2020).

172. Austin, W., Turrell, W. & Tilbrook, C. A brief history of Scottish blue carbon science and the Scottish Blue Carbon Forum: Where next? in.

173. Burrows, M. et al. Assessment of carbon capture and storage in natural systems within the English North Sea (Including within Marine Protected Areas). (2021).

174. Mariani, G. et al. Let more big fish sink: Fisheries prevent blue carbon sequestration—half in unprofitable areas. Science Advances 6, eabb4848.

175. Pershing, A. J., Christensen, L. B., Record, N. R., Sherwood, G. D. & Stetson, P. B. The Impact of Whaling on the Ocean Carbon Cycle: Why Bigger Was Better. PLOS ONE 5, e12444 (2010).

176. Christianson, A. B. et al. The promise of blue carbon climate solutions: where the science supports ocean-climate policy. Frontiers in Marine Science 589 (2022).

177. Durfort, A. et al. Recovery of carbon benefits by overharvested baleen whale populations is threatened by climate change. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 289, 20220375 (2022).

178. Tulloch, V. J. D., Plaganyi, E. E., Brown, C., Richardson, A. J. & Matear, R. Future recovery of baleen whales is imperiled by climate change. Global Change Biology 25, 1263–1281 (2019).

179. Bijma, J., Portner, H.-O., Yesson, C. & Rogers, A. D. Climate change and the oceans – What does the future hold? Marine Pollution Bulletin 74, 495–505 (2013).

180. Wright, P., Pinnegar, J. & Fox, C. Impacts of climate change on fish, relevant to the coastal and marine environment around the UK. 354–381 (2020).

181. Gormley, K. et al. Connectivity and Dispersal Patterns of Protected Biogenic Reefs: Implications for the Conservation of Modiolus modiolus (L.) in the Irish Sea. PLOS ONE 10, e0143337 (2015).

182. Hiscock, K. Exploring Britain’s Hidden World: A Natural History of Seabed Habitats. (2018).

183. Edwards, M. et al. Plankton, jellyfish and climate in the North-East Atlantic. MCCIP Sci. Rev 2020, 322–353 (2020).

184. Fromentin JM & Planque B. Calanus and environment in the eastern North Atlantic. II. Influence of the North Atlantic Oscillation on C. finmarchicus and C. helgolandicus. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 134, 111–118 (1996).

185. Engelhard, G. H., Righton, D. A. & Pinnegar, J. K. Climate change and fishing: a century of shifting distribution in North Sea cod. Global Change Biology 20, 2473–2483 (2014).

186. Evans, P. G. H. & Waggitt, J. J. Impacts of climate change on marine mammals, relevant to the coastal and marine environment around the UK (MCCIP Science Review 2020).

187. Vezzulli, L. et al. Climate influence on Vibrio and associated human diseases during the past half-century in the coastal North Atlantic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, E5062–E5071 (2016).

188. Walsh, J. E. et al. The high latitude marine heat wave of 2016 and its impacts on Alaska. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc 99, S39–S43 (2018).

189. IPCC. Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. 151 (2014).

190. Mahaffey, C., Palmer, M., Greenwood, N. & Sharples, J. Impacts of climate change on dissolved oxygen concentration relevant to the coastal and marine environment around the UK. MCCIP Science Review 31–53 (2020).

191. Smith, K. E. et al. Biological Impacts of Marine Heatwaves. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. (2023).

192. Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Marine Heatwaves. Annu.Rev. Mar. Sci. 13, 313–342 (2021).

193. Bell, J. J. et al. Marine heat waves drive bleaching and necrosis of temperate sponges. Current Biology 33, 158-163.e2 (2023).

194. Leon, P. et al. Relationship between shell integrity of pelagic gastropods and carbonate chemistry parameters at a Scottish Coastal Observatory monitoring site. ICES Journal of Marine Science 77, 436–450 (2020).

195. Findlay, H. et al. Climate change impacts on ocean acidification relevant to the UK and Ireland. MCCIP Science Review 2 (2022).

196. Wolf, J., Woolf, D. & Bricheno, L. Impacts of climate change on storms and waves relevant to the coastal and marine environment around the UK. MCCIP Science Review 2020, 132–157 (2020).

197. Vanem, E. & Bitner-Gregersen, E. M. Stochastic modelling of long-term trends in the wave climate and its potential impact on ship structural loads. Applied Ocean Research 37, 235–248 (2012).

198. Bitner-Gregersen, E. M., Eide, L. I., Horte, T. & Skjong, R. Potential Impact of Climate Change on Design of Ship and Offshore Structures. in Ship and Offshore Structure Design in Climate Change Perspective 43–52 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013).

199. Thompson, R. C. et al. Lost at Sea: Where Is All the Plastic? Science 304, 838–838 (2004).

200. Stafford, R. & Jones, P. J. S. Viewpoint – Ocean plastic pollution: A convenient but distracting truth? Marine Policy 103, 187–191 (2019).

201. Ford, H. V. et al. The fundamental links between climate change and marine plastic pollution. Science of The Total Environment 806, 150392 (2022).

202. Bergmann, M. et al. Plastic pollution in the Arctic. Nat Rev Earth Environ 3, 323–337 (2022).

203. Wyllie, J. Oil industry dumping tons of microplastics into North Sea each year. Press and Journal (2018).

204. Knutsen, H. et al. Microplastic accumulation by tube-dwelling, suspension feeding polychaetes from the sediment surface: A case study from the Norwegian Continental Shelf. Marine Environmental Research 161, 105073 (2020).

205. La Beur, L. et al. Baseline Assessment of Marine Litter and Microplastic Ingestion by Cold-Water Coral Reef Benthos at the East Mingulay Marine Protected Area (Sea of the Hebrides, Western Scotland). Frontiers in Marine Science 6, (2019).

206. Wright, S. L., Rowe, D., Thompson, R. C. & Galloway, T. S. Microplastic ingestion decreases energy reserves in marine worms. Current Biology 23, R1031–R1033 (2013).

207. Roman, L., Schuyler, Q., Wilcox, C. & Hardesty, B. D. Plastic pollution is killing marine megafauna, but how do we prioritize policies to reduce mortality? Conservation Letters 14, e12781 (2021).

208. Adyel, T. M. & Macreadie, P. I. Plastics in blue carbon ecosystems: a call for global cooperation on climate change goals. The Lancet Planetary Health 6, e2–e3 (2022).

209. Smith, M., Love, D. C., Rochman, C. M. & Neff, R. A. Microplastics in Seafood and the Implications for Human Health. Current Environmental Health Reports 5, 375–386 (2018).

210. Bauer, F. & Fontenit, G. Plastic dinosaurs – Digging deep into the accelerating carbon lock-in of plastics. Energy Policy 156, 112418 (2021).

211. Carpenter, S. Why The Oil Industry’s $400 Billion Bet On Plastics Could Backfire. Forbes (2020).

212. Lo, J. Plastics resolution tees up battle over oil industry’s plan B, Climate Home News. Climate Home News (2022).

213. Oceana. The Cost of Amazon’s Plastic Denial on the World’s Oceans. (2022).

214. BP. BP Energy Outlook – 2018 edition. (2018).

215. Shell. 4 Segment information - Shell Annual Report 2020. (2021).

216. International Energy Agency. The Future of Petrochemicals, (2018).

217. BEIS. UK Offshore Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment 4 (OESEA4).

218. CIEEM. The Guidelines for Ecological Impact Assessment in the UK and Ireland. (2018).

219. Barker, A. & Jones, C. A critique of the performance of EIA within the offshore oil and gas sector. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 43, 31–39 (2013).

220. Hancox, E. QUALITY REVIEW OF OFFSHORE PETROLEUM DEVELOPMENT ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENTS AGAINST THE EIA DIRECTIVE. 50 (2019).

221. Clark, M. R., Durden, J. M. & Christiansen, S. Environmental Impact Assessments for deep-sea mining: Can we improve their future effectiveness? Marine Policy 114, (2020).

222. OSPAR. Status Assessment 2022 - Deep-sea sponge aggregations. (2022).

223. OPRED. Environmental Statement Summary - Alligin Development.(2018).

224. BP. BP announces first oil from Alligin field, west of Shetland | News and insights | Home.

225. BEIS & OPRED. Offshore Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA): An overview of the SEA process. (2023).

226. Currie, D. R. & Isaacs, L. R. Impact of exploratory offshore drilling on benthic communities in the Minerva gas field, Port Campbell, Australia. Marine Environmental Research 59, 217–233 (2004).

227. Ellis, J., Fraser, G. & J, R. Discharged drilling waste from oil and gas platforms and its effects on benthic communities. Marine Ecology Progress Series 456, 285–302 (2012).

228. Gates, A. R. & Jones, D. O. B. Recovery of Benthic Megafauna from Anthropogenic Disturbance at a Hydrocarbon Drilling Well (380 m Depth in the Norwegian Sea). PLOS ONE 7, e44114 (2012).

229. Stein J E, Reichert W L, & Varanasi U. Molecular epizootiology: assessment of exposure to genotoxic compounds in teleosts. Environmental Health Perspectives 102, 19–23 (1994).

230. Gerrard, S., Grant, A., Marsh, R. & London, C. Drill cuttings piles in the North Sea: management options during platform decommissioning. Centre for Environmental Risk, Res. Rpt (1999).

231. Helm, R. C. et al. Overview of effects of oil spills on marine mammals. Handbook of oil spill science and technology 455–475 (2014).

232. Venn-Watson, S. et al. Adrenal Gland and Lung Lesions in Gulf of Mexico Common Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) Found Dead following the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. PLOS ONE 10, e0126538 (2015). 233. OSPAR. Precautionary Principle. (2022).

234. Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (2022). (2022).

235. Linde, L., Sanchez, F., Mete, G. & Lindberg, A. North Sea oil and gas transition from a regional and global perspective. (2022).

236. NSW Government. NSW Government rules out commercial offshore exploration and mining. (2022).

237. Government of Canada. Protection Standardsto better conserve our oceans. (2022).

238. Kapoor, A., Fraser, G. S. & Carter, A. Marine conservation versus offshore oil and gas extraction: Reconciling an intensifying dilemma in Atlantic Canada. The Extractive Industries and Society 8, 100978 (2021).

239. Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Backgrounder: Laurentian Channel Marine Protected Area. (2019).

240. Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. Regulations. (No date).

241. Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument Permitting. (No date).

242. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Activities and use. (2022).

243. Jaspars, M. et al. The marine biodiscovery pipeline and ocean medicines of tomorrow. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 96, 151–158 (2016).

244. Hyder, K., Maravelias, C. D., Kraan, M., Radford, Z. & Prellezo, R. Marine recreational fisheries — current state and future opportunities. ICES Journal of Marine Science 77, 2171–2180 (2020).

245. White, M. P., Elliott, L. R., Gascon, M., Roberts, B. & Fleming, L. E. Blue space, health and well-being: A narrative overview and synthesis of potential benefits. Environmental Research 191, 110169 (2020).

246. Venegas-Li, R. et al. Global assessment of marine biodiversity potentially threatened by offshore hydrocarbon activities. Global Change Biology 25, 2009–2020 (2019).

247. Gattuso, J.-P. et al. Ocean solutions to address climate change and its effects on marine ecosystems. Frontiers in Marine Science 337 (2018).

248. IAMMWG, C. C. & Siemensma, M. A Conservation Literature Review for the Harbour Porpoise (Phocoena phocoena). JNCC Report (2015).

249. Evans, P. & Waggitt, J. Impacts of climate change on Marine Mammals, relevant to the coastal and marine environment around the UK. (2020).

250. HELCOM. Red List of Baltic Sea underwater biotopes, habitats and biotope complexes. (2013).

251. Borrell, A. PCB and DDT in blubber of cetaceans from the northeastern north Atlantic. Marine Pollution Bulletin 26, 146–151 (1993).

252. Law, R. J. & Whinnett, J. A. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in muscle tissue of harbour porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) from UK waters. Marine Pollution Bulletin 24, 550–553 (1992).

253. Heuvel-Greve, M. J. van den et al. Polluted porpoises: Generational transfer of organic contaminants in harbour porpoises from the southern North Sea. Science of The Total Environment 796, 148936 (2021).

254. Graham, I. M. et al. Harbour porpoise responses to pile-driving diminish over time. Royal Society Open Science 6, 190335 (2019).

255. Todd, V. L., Williamson, L. D., Couto, A. S., Todd, I. B. & Clapham, P. J. Effect of a new offshore gas platform on harbor porpoises in the Dogger Bank. Marine Mammal Science 38, 1609–1622 (2022).

256. Jarvela Rosenberger, A. L., MacDuffee, M., Rosenberger, A. G. J. & Ross, P. S. Oil Spills and Marine Mammals in British Columbia, Canada: Development and Application of a Risk-Based Conceptual Framework. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 73, 131–153 (2017).

257. Helm, R. C. et al. Overview of Effects of Oil Spills on Marine Mammals. in Handbook of Oil Spill Science and Technology 455–475 (2014).

258. Williams, R. et al. Levels of polychlorinated biphenyls are still associated with toxic effects in harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) despite having fallen below proposed toxicity thresholds. Environmental Science & Technology 54, 2277–2286 (2020).

259. Santos, M. & Pierce, G. The diet of harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) in the Northeast Atlantic. Oceanogr Mar Biol Annu Rev 41, 355–390 (2003).

260. Hogg, M. et al. Deep-sea sponge grounds: reservoirs of biodiversity. UNEP-WCMC biodiversity series 32, 1–86 (2010).

261. Lea-Anne Henry & Roberts, J. Applying the OSPAR habitat definitions of deep-sea sponge aggregations to verify suspected records of the habitat in UK waters. 508 (2014).

262. Cathalot, C. et al. Cold-water coral reefs and adjacent sponge grounds: hotspots of benthic respiration and organic carbon cycling in the deep sea. Frontiers in Marine Science 2, (2015).

263. JNCC. North-east Faroe-Shetland Channel MPA: Supplementary Advice on the Conservation Objectives (SACO). (2018).

264. Howell, K., Davies, J. & Narayanaswamy, B. Identifying deep sea megafaunal epibenthic assemblages for use in habitat mapping and marine protected area network design. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 90, 33–68 (2010).

265. ICES. A suggestive list of deep-water VMEs and their characteristic taxa. https://www.ices.dk/data/Documents/VME/VMEs%20and%20 their%20taxa.pdf (2020).

266. ICES. ICES/NAFO JOINT WORKING GROUP ON DEEP-WATER ECOLOGY (WGDEC). file:///C:/ Users/owner/Downloads ICESNAFOJointWorkingGrouponDeepwaterEcologyWGDEC_Republished.pdf (2020).

267. Indraningrat, A. A. G., Smidt, H. & Sipkema, D. Bioprospecting Sponge-Associated Microbes for Antimicrobial Compounds. Marine Drugs 14, (2016).

268. Cooley, S. et al. Oceans and coastal ecosystems and their services In: in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of the WGII to the 6th assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change IPCC AR6 WGII (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

269. Daniel O. B. Jones, Ian R. Hudson, & Brian J. Bett. Effects of physical disturbance on the cold-water megafaunal communities of the Faroe–Shetland Channel. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 319, 43–54 (2006).

270. Tjensvoll I, Kutti T, Fosså JH, & Bannister RJ. Rapid respiratory responses of the deep-water sponge Geodia barretti exposed to suspended sediments. Aquat Biol 19, 65–73 (2013).

271. Henry, L.-A., Harries, D., Kingston, P. & Roberts, J. M. Historic scale and persistence of drill cuttings impacts on North Sea benthos. Marine Environmental Research 129, 219–228 (2017).

272. BBC News. Cambo oil field project ‘could jeopardise deep sea life’. BBC News (2021).

273. SICCAR POINT ENERGY. 2021. Cambo Oil Field, UKCS Blocks 204/4a, 204/5a, 204/9a and 204/10a Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/991817/D-4261-2021_-_ES.pdf (2021).

274. Webster, L. et al. Monitoring of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Scottish Deepwater environments. Marine Pollution Bulletin 128, 456–459 (2018).

275. Luter, H. M. et al. The Effects of Crude Oil and Dispersant on the Larval Sponge Holobiont. mSystems 4, e00743-19 (2019).

276. Kahn, A. S., Yahel, G., Chu, J. W. F., Tunnicliffe, V. & Leys, S. P. Benthic grazing and carbon sequestration by deep-water glass sponge reefs. Limnology and Oceanography 60, 78–88 (2015).

277. Guihen, D., White, M. & Lundälv, T. Temperature shocks and ecological implications at a cold-water coral reef. Marine Biodiversity Records 5, (2012).

278. OSPAR Commission. Background Document for Ocean quahog Arctica islandica. https:// qsr2010.ospar.org/media/assessments/Species/ P00407_Ocean_quahog.pdf (2010).

279. JNCC and Natural England. Review of the MCZ Features of Conservation Importance. https://data.jncc.gov.uk/data/94f961af-0bfc4787-92d7-0c3bcf0fd083/MCZ-review-foci201605-v7.0.pdf (2016).

280. Garcia, S. et al. Protecting the North Sea: Holderness. 32 (2019).

281. Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs. Conservation Objectives and Potential Management Options: Outer Belfast Lough Marine Conservation Zone (MCZ). https://niopa. qub.ac.uk/bitstream/NIOPA/5164/1/Conservation%20Objectives%20and%20Potential%20 Management%20Options%20-%20Outer%20 Belfast%20Lough%20MCZ_0.pdf (2016).

282. Hawes, J., Noble-James, T., Lozach, S., Archer-Rand, S., & Cunha, A. North East of Farnes Deep Marine Conservation Zone (MCZ) Monitoring Report 2016.

283. Mazik, K, S. N. et al. A review of the recovery potential and influencing factors of relevance to the management of habitats and species within Marine Protected Areas around Scotland. (2015).

284. Offshore Petroleum Regulator for Environment and Decommissioning. Talbot Field Development. https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications/talbot-field-development (2022).

285. Steimle, F.W., Boehm, P.D., Zdanowicz, V.S., & Bruno, R.A. Organic and trace metal levels in ocean quahog, Arctica islandica Linne, from the Northwestern Atlantic. FISHERY BULLETIN 84, (1986).

286. Tyler-Walters, H. & Hiscock, K. Arctica islandica Icelandic cyprine. In Tyler-Walters H. and Hiscock K. (eds) Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Reviews. Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. in (2017).

287. Ridgway, I. D. & Richardson, C. A. Arctica islandica: the longest lived non colonial animal known to science. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 21, 297–310 (2011).

288. Butler, P. G., Wanamaker, A. D., Scourse, J. D., Richardson, C. A. & Reynolds, D. J. Variability of marine climate on the North Icelandic Shelf in a 1357-year proxy archive based on growth increments in the bivalve Arctica islandica. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 373, 141–151 (2013).

289. Estrella-Martínez, J. et al. Reconstruction of Atlantic herring ( Clupea harengus ) recruitment in the North Sea for the past 455 years based on the δ 13 C from annual shell increments of the ocean quahog ( Arctica islandica ). Fish and Fisheries 20, (2019).

290. Butler, P. G. et al. Is there a reliable taphonomic clock in the temperate North Atlantic? An example from a North Sea population of the mollusc Arctica islandica. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 560, 109975 (2020).

291. Arellano-Nava, B. et al. Destabilisation of the Subpolar North Atlantic prior to the Little Ice Age. Nature Communications 13, 5008 (2022).

292. Stott, K. et al. The potential of Arctica islandica growth records to reconstruct coastal climate in north west Scotland, UK. Quaternary Science Reviews 29, 1602–1613 (2010).

293. Liehr, G. A., Zettler, M. L., Leipe, T. & Witt, G. The ocean quahog Arctica islandica L.: a bioindicator for contaminated sediments. Marine Biology 147, 671–679 (2005).

294. OSPAR Commission. List of Threatened and/or Declining Species & Habitats. OSPAR Commission https://www.ospar.org/work-areas/ bdc/species-habitats/list-of-threatened-declining-species-habitats (2008).

295. Witbaard, R. & Bergman, M. J. N. The distribution and population structure of the bivalve Arctica islandica L. in the North Sea: what possible factors are involved? Journal of Sea Research 50, 11–25 (2003).

296. Ballesta-Artero, I., Janssen, R., Meer, J. van der & Witbaard, R. Interactive effects of temperature and food availability on the growth of Arctica islandica (Bivalvia) juveniles. Marine Environmental Research 133, 67–77 (2018).

297. Brey, T., Arntz, W. E., Pauly, D. & Rumohr, H. Arctica (Cyprina) islandica in Kiel Bay (Western Baltic): growth, production and ecological significance. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 136, 217–235 (1990).

298. JNCC. Faroe-Shetland Sponge Belt Nature Conservation Marine Protected Area: Data Confidence Assessment. https://data.jncc. gov.uk/data/411ea794-b135-4877-9fc8-e3e6c054eef9/FSSB-2-DataConfidenceAssessment-v5.0.pdf (2014).

Didascalie immagini:

* Copertina: Coralli delle acque fredde.

- Impatto delle attività petrolifere e di estrazione del gas offshore nel Regno Unito sulle comunità di spugne di acque profonde

- L'estrazione del petrolio e gas alimentano la crisi della plastica

- Primo piano delle microplastiche recuperate dall'oceano